Challenging Notions of Indian Dance in the Netherlands

In the late 1970s, when I was growing up, the Indian community was small, with only a few families residing in the country. My mother, Sharadha Raghuraman, was one of the pioneers in introducing Bharatanatyam in the Netherlands, leading one of the first Bharatanatyam schools: Noopur Dance School. She not only taught and performed herself, but also nurtured a group of students who went on to perform as well. This environment enabled me to grow up surrounded by dance and to take the stage from the age of five.

However, when I reflect on it, my dance journey sometimes feels like it has come full circle. The challenges early migrants like my mother faced and what I faced growing up are continuing – however there are some significant changes to be found. Establishing Indian dance at a professional level in the Netherlands has been, and continues to be, a challenging journey.

Although the Netherlands is home to diverse ethnic communities, the Indian diaspora has only recently begun to grow in significant numbers. For example, despite gaining considerable knowledge and inspiration from my mother and her activities, the opportunities to witness performances by artists from India when I was growing up were extremely limited. Typically, only one or two Indian dance artists would tour the Netherlands each year, rendering the cultural landscape relatively barren in terms of inspiration for me.

When looking at the Indian dance community in the Netherlands, the Surinam Hindustanis have been and still are of significant relevance— they are descendants of Indian laborers who migrated via Suriname during colonial times. This community of Surinam Hindustanis had a strong interest in Indian culture and at the time when my mother was teaching and when I started to develop myself as a Bharatanatyam dancer, there were a group of dancers from this community who really were working hard at mastering the form. Some of them are still active today, mostly as teachers. And there are also younger generation dancers from this community active today, mostly in the hobby or semi-professional sphere while a few of them are emerging choreographers.

Transformative Experience in India

In 1997, I traveled to India to conduct research for my master’s degree in cultural anthropology at the University of Leiden. My research focused on the changing modes of knowledge transmission and their impact on the form of Bharatanatyam, particularly the evolving relationship between guru and student. This experience allowed me to continue dancing while deepening my academic pursuits. Immersed in an environment rich with dance and music, I spent each day learning dance, conducting interviews, and performing.

During this year, I studied intensively with Guru Padmini Ravi in Bangalore, while also interviewing other dance teachers for my thesis. This exposure to high-level training, interaction with dancers of my generation, and opportunities to participate in choreography and performances significantly broadened my horizons and deepened my connection to dance.

Returning to the Netherlands: Pioneering a Path

Upon returning to the Netherlands in late 1997, I was filled with new skills, dance material, and a deep sense of inspiration. Determined to create opportunities, I organized my own dance tours, managed visas for Indian musicians, and curated my dance repertoire. In doing so, I simultaneously assumed the roles of tour manager, production coordinator, PR manager, and performing artist. From 1997 to 2001, this self-managed approach taught me invaluable skills, fostering confidence and resilience that continue to benefit me to this day.

However, promoting Bharatanatyam in the Dutch theatre scene posed significant challenges. Convincing theatres of the cultural and artistic value of Bharatanatyam, with its intricate histories and contemporary relevance, required breaking stereotypes and encountering clichéd perceptions of Indian dance. Despite these obstacles, I received crucial support from open-minded programmers and directors who recognized the importance of diverse perspectives and aesthetics. Nevertheless, my work was often presented within the narrow context of “Indian culture,” which increasingly felt limiting.

Evolving Artistic Vision and Expanding Form

As my artistic vision matured, I realized that working exclusively within the framework of Bharatanatyam constrained my creative expression. In 2002, I began exploring ways to question and expand the form, seeking to discover my own voice while building on the powerful skills and traditions of my dance background. Navigating the complexities of the contemporary dance scene and funding landscape—where Indian dance was not widely acknowledged as a professional form—I eventually found an opportunity at Danswerkplaats Amsterdam. With them I secured funding to initiate research that would help me develop my own artistic vision.

This marked the beginning of a new creative journey. My focus shifted from validating Indian dance’s cultural relevance to exploring how elements of Bharatanatyam could contribute to contemporary dance. This required a deeper understanding of my motivations and the unique perspectives I could bring to the dance scene. During this period, my creative process was largely a solo endeavor, using my own body as a site of research and exploration.

Cross-Cultural Exploration: The Mali Experience

This journey of artistic exploration led me to another cultural crossroads—I became deeply interested in West African culture, particularly the music and dance traditions of the Mandinka people. Observing the prevalence of North-South cultural exchanges (e.g., UK- India) and the scarcity of South-South dialogues (e.g., India-Mali), I embarked on a research trip to Mali, supported by a grant. I had the privilege of studying there supported by the late Kora virtuoso and Grammy award winner Toumani Diabaté, who graciously hosted me and facilitated my learning experience.

This two-month immersion into Mandinka music and dance profoundly influenced my artistic vision, introducing me to new rhythmic structures and movement philosophies.

Upon returning to the Netherlands, I continued experimenting with Mandinka elements while simultaneously exploring innovative ways to play with Bharatanatyam. Going to Mali helped me see the importance of African aesthetics and so when I met African choreographer Serge-Aimé Coulibaly from Burkina Faso (Faso Danse Theatre), I was very inspired to see how he had developed techniques to open up the dance and music traditions of his region and beyond. His approach and vision deeply influenced me in my own work in the years to come.

Collaborative Creations and Breaking Boundaries

Recognizing the limitations of solo work, I began involving other dancers, initially focusing on Bharatanatyam practitioners. In 2008, I received funding for my first solo contemporary production, “In Between Skin,” which premiered at the Cadance Festival at the Korzo Theatre—an important platform for choreographers in the Netherlands. This marked a significant turning point, leading to a productive collaboration with Korzo’s then-director, Leo Spreksel. His understanding of Indian dance’s potential and his willingness to support my vision opened new avenues for my work. Our conversations also led to the beginning of the India Dance Festival at the Korzo theatre, which I helped co-curate.

Kalpanarts: Establishing a New Trajectory with Institutional Support and Recognition

In 2009, conversations with the Dutch Fund for Performing Arts highlighted the challenges faced by choreographers who defy conventional dance categories. Meanwhile, the city of The Hague expressed interest in my potential role as a rolemodel for the young Indian dance community. This unique alignment of interests—between Korzo’s support, The Hague’s community engagement goals, and the Dutch Fund’s openness to new artistic directions — culminated in a pioneering funding structure in 2011-2012. This provided me with institutional backing to develop Indian-inspired contemporary work within a mainstream context.

During this period, I worked with three Bharatanatyam dancers—Usha Kanagasabi, Anuradha Pancham, and Indu Panday—who demonstrated remarkable talent and dedication, including traveling to India for advanced training. My choreographic approach followed two parallel lines: one focused on deconstructing and reimagining Bharatanatyam with these dancers, while the other involved collaborating with contemporary dancers to create a hybrid movement language that blended elements of Bharatanatyam with Western contemporary dance techniques.

Working with dancers who were not trained in Bharatanatyam, or any other Indian dance form, marked a significant shift. This approach facilitated a novel exploration of the form and required the development of a communicative language through which the dancers could embody the intended energy and vision. Crucially, this was achieved without reducing the form to stereotypical interpretations centred solely on the cliché references of Indian hand gestures and footwork.

After my grant period finished in 2012, I was able to continue my collaboration with Korzo as an artist in residence. There was less money available, yet I could continue with my two-pronged approach of working with both Indian and western contemporary dancers.

By 2015, the tides were shifting, and change was in the air. I noticed that as much as I was being supported by Korzo, I was also dealing with a situation where I did not have my autonomous space. It was time to leave the comfort of this dance house. I met Gysele ter Berg, a dynamic and artistically inclined manager who was very excited to embark on a new adventure with me. With gratitude to Korzo and Leo Spreksel, I took a leap of faith and joined forces with Gysele and we created Kalpanarts at the end of 2015.

We immediately applied for structural funding from the City of The Hague for the period 2017-2020 and were fortunate to receive this support. This pivotal moment marked my transition from being part of a larger institution, bound by its established agenda, to leading my own company. This newfound autonomy allowed me to collaboratively shape my artistic vision with my manager, fundamentally shifting the power dynamics and granting me greater creative freedom and empowerment. However, as a small organization rooted in dance traditions from marginalized communities, we remain significantly influenced by those who control financial resources and performance opportunities. Despite these challenges, the movement from the margins toward the centre began in a dynamic and promising way, positioning us to challenge existing norms and expand the boundaries of the dance landscape.

One of the key challenges we faced during this transition was the scarcity of full-time, Indian-trained dancers in the region. At the time, there were only two professional Indian dancers available: Indu Panday, the sole dancer remaining from the original trio I had worked with, and Sooraj Subramaniam, based in Belgium. This presented a difficult choice: I could either work exclusively with these two dancers, which would limit the scale and scope of the productions I wished to create, or I could include Western-trained dancers to bring the larger group pieces I envisioned to life.

Opting for the latter, however, meant that I could no longer exclusively feature dancers of Indian or non-Western descent, which had been one of my original goals—namely, to showcase dancers of colour and those trained in traditions other than Western contemporary dance. Ultimately, I chose to prioritize the ability to bring larger works to fruition and to share the techniques of Indian dance with dancers who had not been previously exposed to Bharatanatyam. While this decision represented a departure from some of my earlier intentions, it was one made with the broader vision of advancing the work and exploring new ways of engaging with dance forms beyond their traditional boundaries.

In 2021, our structural grant support was extended for an additional four years from the City of The Hague and we also got funding from the Dutch Fund for Performing Arts, covering the period from 2021 to 2024. This expansion of support has facilitated the opening of new avenues for the growth and development of our artistic work and vision, allowing us to further integrate into the broader mainstream dance and cultural landscape in the Netherlands.

Engaging with Dance Histories

A pivotal influence on my artistic journey has been Dr. Priya Srinivasan, whose thinking on critical dance studies has fundamentally reshaped my perspective on Indian dance. Her approach and ongoing dialogues with me over the past 12 years have encouraged me to engage more deeply with the complex histories of Indian dance, particularly Bharatanatyam, prompting me to reflect on my responsibility as an artist of Indian descent to acknowledge and reveal these layered narratives. This engagement has not only transformed my creative process but also challenged me to thoughtfully incorporate historical complexities into my work.

Additionally, my choice to collaborate with Western contemporary dancers is a deliberate choice to rethink the application of Indian dance techniques. This approach serves two purposes: it explores the potential of these techniques isolated from its history while simultaneously honouring their historical significance by fostering their continued evolution.

In this way, I seek to create a dynamic dialogue between tradition and innovation, enriching the contemporary dance landscape.

Navigating Stereotypes and Expanding Horizons

As we continue to build the company and refine our artistic vision, it is striking to note that, despite the passage of over two decades, many of the challenges I encountered when first introducing Bharatanatyam to theatre and festival programmers in the late 1990s, persist.

The persistent reliance on stereotypical and clichéd representations of non-Western dance and culture remains prevalent. As my work has evolved into a more hybrid form, I still encounter expectations shaped by these limited frameworks. Specifically, there is an ongoing tendency to either align my work with the conventions of Western contemporary dance or to reduce it to orientalist assumptions about “Indian dance.” Neither of these reductive perspectives align with my vision or the artistic contributions I seek to offer through Kalpanarts. Having said this, we are able to reach a wide and diverse audience, expanding their understanding of dance and theatre beyond the Western framework through performances by a multicultural cast. I aspire to continue making a meaningful impact on the field through my company’s vision. The relevance of our work is proven by a new opening that has come up. The Dutch National Ballet has given me a 2-year position (2024-2026) as creative associate: a role never offered to a choreographer outside the ballet world before. I strive to keep opening the minds (and bodies) of all artists, creatives and audiences. I also continue to curate Korzo theatre’s vision of what Indian dance might look like embedded within its regular programming, especially after the India Dance Festival ended last year (2024). Keeping my fingers in multiple communities of dance helps me bring them together.

This journey reflects the evolution of Indian dance in the Netherlands from a culturally specific form to an innovative and dynamic contemporary practice. Through persistent exploration, cross-cultural dialogues, and strategic collaborations, I have been able to negotiate space for Indian-inspired work within the mainstream dance landscape. This endeavor not only challenges stereotypical representations but also contributes to a richer and more inclusive artistic ecosystem.

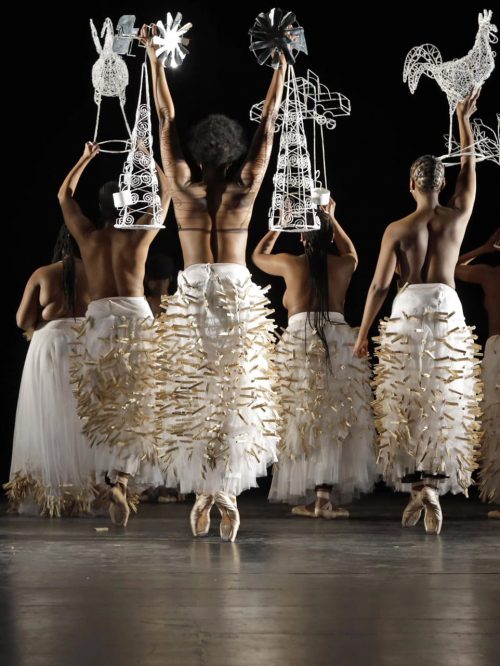

Cover Photo: Kalpana Raghuraman in The Spirit of Frida. Kalpana Raghuraman & Korzo Producties. Photo: Robert Benschop.

Bio

Kalpana Raghuraman is a dancer, choreographer, and anthropologist. Born and raised in the Netherlands with Indian roots, she is a leading expert in the traditions, cultures, and sociology of Indian dance. Her mother Sharadha Raghuraman was the pioneer who started the first Bharatanatyam school in the Netherlands and Kalpana continues the legacy by being the first Indian choreographer to lead a dance company that is part of the mainstream dance scene in the Netherlands. Within the vibrant Dutch dance scene, Kalpana distinguishes herself with a hybrid dance style she developed, inspired by elements of Indian dance and philosophy. In addition to her role as artistic director of Kalpanarts, she is also a creative associate at the Dutch National Ballet for the 2024-2026 season. This marks the first time a ballet company has offered this position to a choreographer from outside the ballet world and to an Indian choreographer. Since 2025 she is also appointed as the curator of the Indian dance and music performances in the regular programming of the Korzo Theater in The Hague.