Embodied. In breaks.

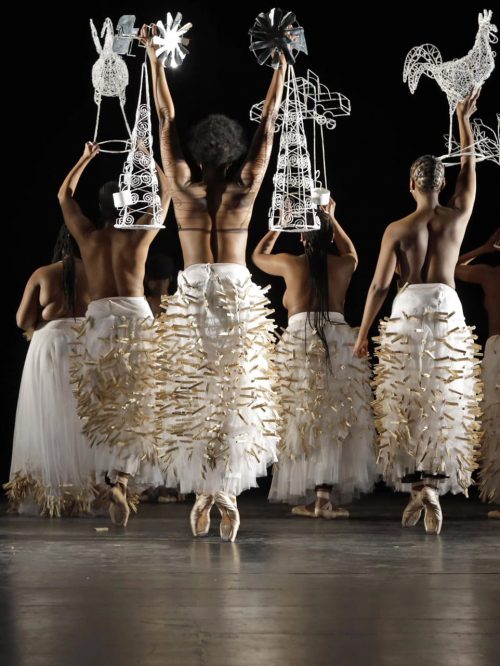

Photo- Choy Ka Fai

We create. Like other artists in my hometown.

But in breaks.

So is this writing.

It was written. In breaks.

In between the breaks, we had police sirens informing us that curfew has begun, ordering people to stay inside or bear the consequences. In between the breaks, we saw smoke rising in the sky, sounds of gunshots and tear gas being fired during protest. We also had internet bans that lasted days, sometimes extending to couple of months. Not that violence and conflict was new, our home (Manipur) has been engulfed in a state of violence since May 2023.

Amidst the clanking of electric pole that serves as people’s clarion call to come out for protests, Embodied grew.

Also, in breaks.

I

Embodied was first performed in March 2020 at the Dharamshala Residential & International Festival for Theatre. It was when fear of Covid was looming gradually. The festival was publicly funded and collectively organized where participating artists, volunteers and organizers stayed at the same apartment, cooked, ate, and slept together. The festival was built as a collective celebration where everyone had a role to play, duties were shared like cleaning, cooking, taking care of techs, light, sound and many more. There was also an aged lady from the neighborhood who would often drop by to give us her homemade jam.

Embodied took shape in this space and time. The first performance ran like a trial with technical errors and audience warmly encouraging the missteps as the performance tried to find its ground. Embodied began as an exploration in 2020 between Surjit Nongmeikapam, a contemporary dancer and choreographer, and Babina Chabungbam, a classical Manipuri dancer who was then doing her research on Manipuri performing arts, especially the Raas Leela (Jagoi Raas) of Manipur. It was based on a simple proposition to translate the research into a performative text. It was an attempt to transcend the realm of the written text while seeking avenues of presenting Manipuri dance differently. One that engages the audience to seek deeper beyond the glittery costumes, embellishments, or a simple joy of watching something ‘exotic’. More importantly, it asks the fundamental question about what constitutes the essence of Manipuri dance.

Embodied presents a panoramic view of dances of Manipur where different snippets are taken from traditional dance forms and modern choreographies. They are assembled in an order that narrates the trajectory of Manipuri dance since the eighteenth century. The performance begins with a short piece from Raas Leela. Raas Leela, often synonymously understood with Manipuri dance is based on Vaishnavite theme of love-play between Krishna, Radha and the cowherd girls. This dance tradition was introduced in Manipur in the eighteenth century when the influence of vaishanvism reached a pinnacle. Given the indigenous (pre-Vaishnavite) revival movement in Manipur today, Raas Leela is seen as a religious colonization of the land, altering its cultural history by erasing the indigenous religion and culture of its people. Embodied attempts to unfold this layer of religious and cultural colonization, quite literally by shedding the layers of costumes on stage. The performance begins with two short dance sequences from Raas Leela and followed by modern dance compositions and the pre-Vaishanvite dance. In each juncture, the layer of costume is shed as though shedding the layers of cultural and religious colonization.

Embodied also presents a personal story of the two dancers. Or rather someone as part of the Manipuri society who grew up embodying its dances through public festivals and ritual dances. Surjit in his contemporary dance practice drew from traditional dances and its philosophical undercurrents. On the other hand, Babina as a traditional dancer not find the rigidity of religion in the dances alone. She would perform the dances based on Vaishnavism and the pre-Vaishnavite dances with same passion. For there was an embodied movements that existed beyond religious hues. In essence the Manipuri dances and movements are considered to derive from nature. There is deep reverence for nature in the cultural conception of cosmology, the festivals, rituals, and its dances. This formed the backbone of Embodied when it began. Initially, it was performed both by Babina and Surjit where Babina danced the embellished Manipuri dances and Surjit portrayed the raw nature from which Manipuri dance is believed to derive from.

II

After a break of 4 years, Embodied was performed again at the Little Stint Festival, New Delhi in March 2024. It changed from its prior format. Because like many of us living in a war zone like situation, the performance also had to change. We lived in constant fear and uncertainty. The violence had penetrated the collective conscience and implanted a collective trauma and thereby rupturing the senses that allow us to create, dance or simply live. We began to ask what will happen to our dances if we all die? Manipuri dances are usually danced as an offering to deities for peace and prosperity of the land. But what happened to the peace that people have been dancing for? Do we feel like dancing even in such times? We are colonized by deep rooted violence, mistrust, and prejudices. Do we still dance when people are dying. In the violence that began in May 2023, thousands have lost their homes, thousands displaced, and many lost their lives.

This is the new space and time Embodied took its new form.

In addition to previous format of traditional dances and the contemporary rawness, Embodied changed the second half of the performance to express the two dancer’s choreographic response to the current times we are living in. Ever since the violence began, festivals were kept on hold, dance events were stopped, the ritual dance festivals were also called for a halt. In short, people stopped dancing.

Two dance segments were added towards the end of the performance, as though attempting to decolonize the violence that had engulfed the very place to which the dances belonged. This segment drew inspiration from traditional dances and song about separation. It speaks of a soul that departs from its physical body after death. The metaphor of bird is used to depict the soul which now seems lost as there is no home to come back to.

Chekla paikharabada

Pombi hanjilakpada

Chekla gi kaidong fam khangdaduna

Pombi kak ngao nakhare

A bird, a soul

Lost

Since the home is no more.

This last piece serves as a tribute to those who lost their loved ones and lost their homes. It is created from a place that reeks of nothing but scent of death, smoke, and loss. To be able to spend a calm ordinary day, basking in the winter sun, doing the most random of things, in a home that one calls one’s own is a luxury not people surviving in the conflict areas can afford. This is not only true for Manipur but also holds true in the global context where conflict, war and violence has led to death and displacement of thousands of people.

The last dance carries an ‘act of leaving behind’ a home and of the impossibility of going back. It embodies an idea of ‘home’ as a metaphor for physical bodies and of a soul leaving the home. In another more hopeful sense, ‘the act of leaving behind’ symbolizes coming out of the collective trauma and violent realities by focusing on the subdued aesthetics and introspective nature of Manipuri dance.

Despite the dark realities, Embodied will grow.

Hopefully.

But most probably, in breaks.

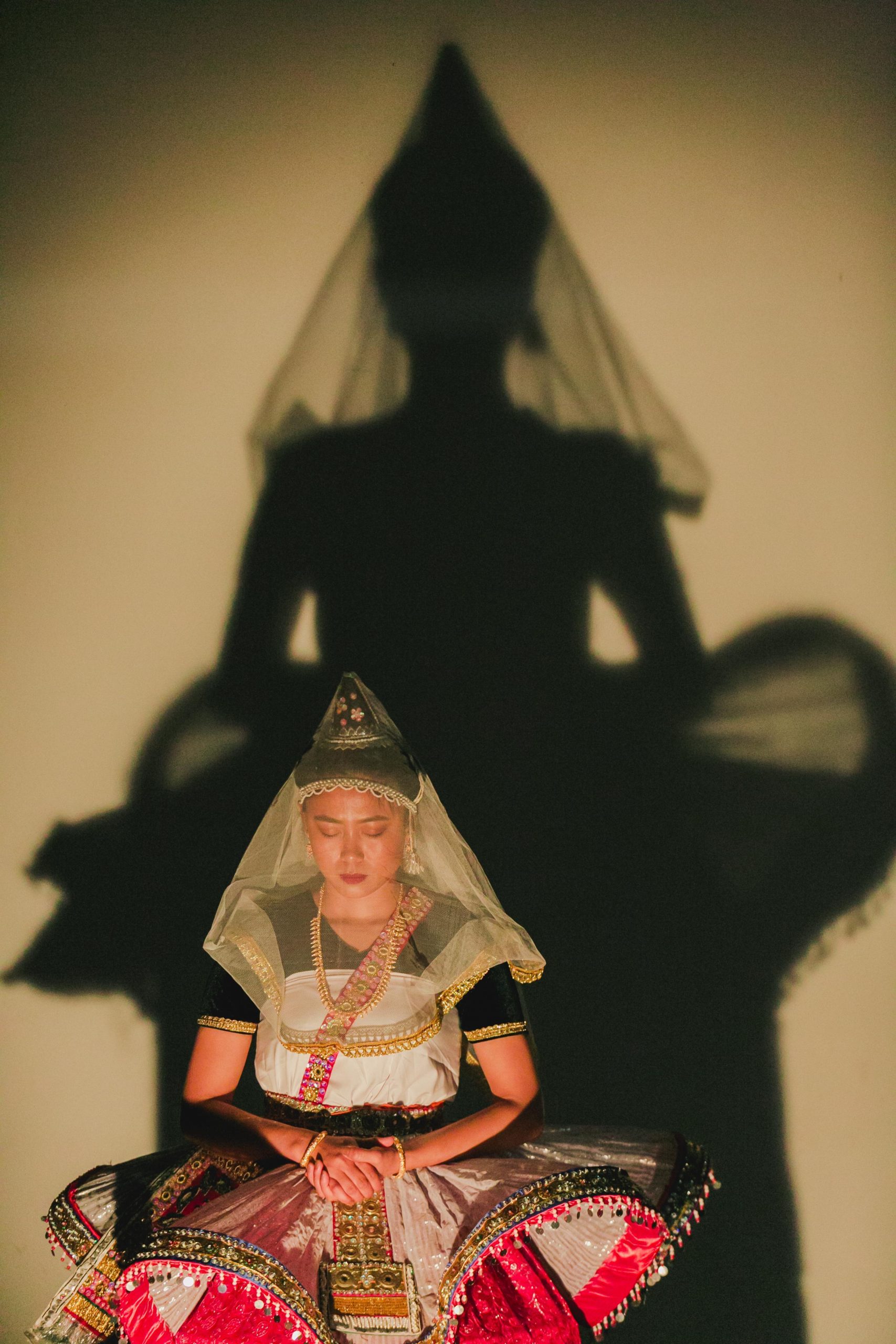

Photo-W.I.P festival

About Embodied

Transcript

Surjit Nongmeikapam – work-in-progress 2024.

A man from Manipur suspends in the mid-air. A visual poem perhaps… he wonders how does it feel to defy gravity, to be floating in time and space. The sounds from his environment surround us like an invitation to enter his realm, a kind of space that people can gather, a space of storytelling and a space of survival in our everyday lives, and a space of silent protest.

Concept/installation/performance by Surjit Nongmeikapam.

Sound by Chaoba Thiyam.

Assistant by Paonam Birjeet.

Video – Choy Ka Fai.

Supported by

Prakriti Foundation and W.I.P.

Bio

Babina Chabungbam is a Manipuri dancer who also engages in research on the performing art traditions of Manipur. She completed her doctoral degree from Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Her doctoral research focused on looking at the Raas Leela as an embodied cultural repertoire to understand the socio-political contestations around the same. An article co-authored with Debanjali Biswas titled “We can’t let go: Navigating dance in (post) conflict society” was published in Conversations Across the field of Dance Studies (2024) and her article “Diba Raas: Story of the Last Raas” was published in the journal Indent: The Body and the Performative (2022). Babina’s dance film “Yum” was awarded by the second position for the Dr Sunil Kothari Award for Emerging Artists (2024)

Surjit Nongmeikapam (Bonbon) is a choreographer and performing artist based in Imphal, Manipur. He began his dance career at the age of 24 and was initially trained in traditional Indian forms and movements before developing an interest in interdisciplinary arts and experimental work. He earned a B.A. in Choreography from the Natya Institute of Kathak and Choreography.

One of the few dancers and choreographers in Manipur actively engaging with contemporary dance, Surjit seeks to promote its development beyond traditional Manipuri culture. He is an award-winning choreographer, having received the PECDA award for his works Nerves (2014) and Folktale (2016). In 2021, he was honored with the AMI Arts Festival Youth Award for Performing Arts. His recent work, Lines and Dots, a collaboration with ASK Dance Company, earned him the Best Choreographer award at the BOH Cameronian Arts Awards in Malaysia in 2025.

His dance film SAMNABA won the Best Cinematography award at The Himalayan Film Festival.

As the artistic director of the Nachom Arts Foundation, Surjit is dedicated to fostering a contemporary dance community in Manipur. He conceptualizes his work as a healing process, blending movement with deep emotional and artistic exploration.

Surjit Nongmeikapam – Methodology

Yangshak movement is an investigation on the philosophy of ‘LAIREN MATHEK’ of the Manipuri martial art form, Thang-Ta (Khuthek Lal Thek) and Dance (Jagoi).

The class will focus on building an in-depth understanding of our body with the help of our, imagination, resonance, impulse and objects. Beyond the physical movements and techniques, the practice will create an avenue for new language that emerges from the body.

Surjit Nongmeikapam always tries to extract from his own dream and create from his imagination. He always wants it to come from “[his] heart”, “which move on [him]” and “closer to [him]”. He wants his work to express his different expressions as a healing process. He tries to keep his artwork alive without any fixed notation or choreography. His notation is not to be attached to one thought. Surjit creates art form, which can be created from the unseen culture of his Manipuri roots. He also makes himself aware not to work from the obvious traditional culture movement. He belongs to contemporary art and loves to create work piece from his dream, imagination, resonance, and objects.