shadowed in neither | nor

In this article I discuss two exemplary phases of my artistic work, referred to as Session #1 tremor of dislocation and Session #2 Beyond Silence.

In my work, I am concerned with the question of how figurations of identity/identities can be created through means of performance that are not clearly nationally delineated, but rather take on gradually fragile and even fluid qualities. Through the burning glass of performance, I address the narrowing of ideas of identity and attributions of belonging that result from my experiences of forced amnesia (forgetting) of origin, ambiguity, disruption and the polyphony of life and personality in order to break the lack of ambiguity of identity attribution and the geographical and historical attributions that go with it. This often concerns emotionally unpleasant and quite disturbing facets that find performative expression.

Essentially, my projects are about coming to terms with a conflict caused by migration, which I initially had to internalize due to my biography. This conflict spans between Namibia and Germany. In my performances and the associated artistic-performative processes, I work with fragments, transitions, gaps, contrasts and questions in order to approach the aforementioned internalized conflict, which for me has to do with a causally contradictory identity: How is identity socially ascribed? What sometimes unsolvable conflicts arise from this for the individual, but also for the collective? This involves tracking down and highlighting normalized and unquestioned lines of power in everyday life – what can language do and what can it not do?

Thereby, geopolitical and biographical aspects intertwine; in my specific case, these are anchored intergenerationally in my own family history on the one hand and in far-reaching geopolitical connections on the other:

-Emigration of German ancestors to former Deutsch-Südwest Afrika after the First World War,

-unresolved after-effects of this ruptured family history caused by the split between Germany and Germany after the Second World War,

-family members living in South-West Africa taking on British and finally South African nationality,

-a life marked by racism and apartheid in South-West Africa until Namibia’s independence in 1991,

-the ongoing festering political conflicts about the continuities of the German colonial legacy in today’s Namibia.

I was born in Windhoek, the capital of South West Africa, now Nambia. At birth, I was registered as South African and white.

I spent my childhood and early youth up to the age of 11 in South-West Africa in a comparatively privileged middle class family. There were no black children in my everyday school life at that time. That only changed in 1978 when my family left South-West Africa. Due to the increasing insecurity caused by SWAPO’s war of independence against the South African apartheid government, my parents along with me and my sister emigrated to West Germany. For my South African father with German roots, who was politically opposed to the apartheid government, it was an emigration to his parents’ country of origin, which was foreign to him; for my mother it was a return to Germany – she comes from the Saarland. For me, born and raised in South West Africa, the move meant emigrating to a foreign country where I experienced what I call “whitewashing”. “Whitewashing” refers to the social experience of fitting into a society or community that is dominantly rooted as German, Central European and defines itself at its core as unquestioningly White, which I experienced as a teenager in West Germany in the late 1970s to 1990s. This subtly violent experience shaped my life.[1]

For me, migration meant being torn out of a geographical location without being able to have a say as an eleven-year-old, and finally ending up in a different landscape and living environment that was completely foreign to me. For me, arriving in Germany meant escaping a civil war zone on the one hand, and yet for many years it brought with it the uncertainty of finding and not finding my way. Previous frames of reference no longer applied, even though I had German ancestors and spoke a German that differed only slightly from continental German. For me, arriving in Germany meant going through many years of irritation. I was white, but not white enough to be considered West German. It was an experiential journey that I aptly describe, with reference to theorist of migration Christou, as “unresolved dislocation”.[2]

————————————————————

[1] Cp. Lilleike, M. „Skinstory – Migratory Experiences and the Transformational Power of Performative Means.“

In: African Somaesthetics: Cultures, Feminisms, Politics. Catherine F. Botha (Ed.), Leiden, Boston: Brill, 2020, P. 200-204. In this essay, I describe the process of social “whitening/whitewashing”, a formative life experience for me that I processed in 2012 in a performance entitled Skinstory/Crossfade – Sound of Migration.

[2] Cp. Christou, A. “(Re)collecting memories, (Re)constructing identities and (Re)creating national landscapes:

spatial belongingness, cultural (dis)location and the search for home in narratives of diasporic

journeys,” International Journal of the Humanities 1 (2003): S. 1455-1464.

The loss of a familiar lifeworld with all its sensory aspects and references collides with completely new sensory references which, if you come from southern Africa, are in no way compatible with the sensory world of experience and the landscape of Germany. If you don’t find an interested, open counterpart, as I experienced as a teenager, but instead meet people who either pity everything that has to do with Africa, devalue it as alienating or exaggerate it as exotic, you begin to conceal what you remember, what is dear to you. Grief settles over what has been left behind. In addition, there is a deep-seated feeling of shame and dread at not having been born in Germany, but in a ‘foreign country’. The place where I come from – that which belongs to my sense of inner self – remains in a constant state of inner upheaval due to the questioning.

Session #1 Tremor of dislocation

The sound of this tremor of dislocation has made its way into my vocal performance work. In Saarland, after my second return to Germany, this time after several years of study in Hawai’i, I got to know the band fliegen und surfen, with Bernd Wegener active as sound performer and drummer, Frank Post on guitar and Guy Winter on bass. They invited me to set off on musical and sonic expeditions. Each session was based on improvisation and the will to give a sonic form to impulses. Sound and vocal impulses met in the quartet to create sonic landscapes acoustically by way of exchange. The shared pleasure consisted of folding and unfolding these landscapes in multi-layered variations through improvisational processes. The resulting timbres and sound patterns were carried by meandering and even driving grooves. Sometimes they splintered explosively and kaleidoscopically, only to suddenly re-figure themselves. In these sessions, I was able to give vocal form to the multi-layered facets of my biographical path and becoming, with all its irritations, angry undertones, shame, fear and dread, as well as to the underlying desire to experiment and the impetuous unknown.

The experiments of Dada, Minimal Music, Extreme Vocalism, Instant Music, Concrete Poetry as well as my stylistically formative experiences with Japanese Noh theater, Chinese opera (jingju) and Hawaiian traditional hula, which I had made through my studies of performing arts and my research in Hawaii and Japan, form the background of my performative vocal actions, which give my dissonant experience of integration an artistic expression, independent of European musical and vocal tradition.

By improvising with flying and surfing, I found access to my repressed kinaesthetic-somatic underlying constitution, which for me had been accompanied by speechlessness for many years. Musically and performatively, I was able to “let speak” my deeply contradictory identity as a person of white skin color born and raised in southern Africa, i.e. in Namibia. The consequences of the civil war of the black population both against the South African occupation that prevailed until 1990 and against the continuities of German colonial influences in the country and my experience of moving from Namibia to Germany as a teenager have shaped my internally trembling self-perception.In my whiteness I feel positively “shadowed” by my perceived identification with the country of Namibia, its people and its history, which fortunately ultimately led to independence. By “shadowed” I mean that there is an underlying Namibian resonance in my self that is difficult to define, which creates an inner critical distance from a “white” German identification that is felt and understood too one-sidedly. For many years, I was unable to live this complexity of my self-perception in Germany. Only the decidedly free musical spirit that connects me with the team of fliegen und surfen opened up the space for me to express the cultural limitations I perceived of not being able to communicate and not being understood. Improvising allowed the possibility of sonic-performative impetus and excess to transcend perceived limitations.

The improvisations with fliegen und surfen attracted their own set of fans. There were also those in the audience who couldn’t stand this form of performance. The sonic facets of the tremor of dislocation, which found expression for me as a vocal performer in the sessions with fliegen und surfen, are startling, frightening, disturbing but at the same time deeply passionate and sometimes quite idiosyncratic and humorously amusing. It is a sound journey that listeners embark on, leaving familiar terrain behind. The unheard and outrageous is not necessarily beautiful – or perhaps it is?

Session #2 Beyond Silence

As a performer, I work with the inner landscape of memories, feelings and sensory realms that hide, emerge and submerge in the non-linguistic domain of the kinaesthetic-somatic world of the self.

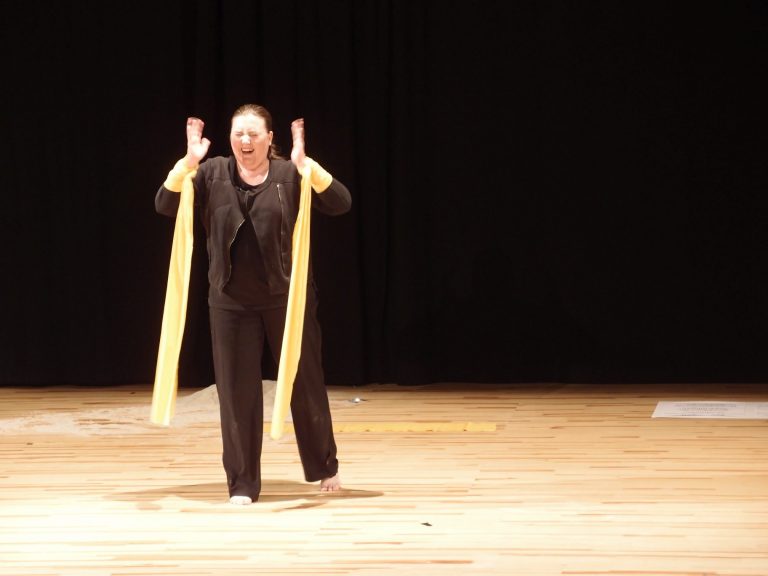

These are dream-like formations, fragments of impressions and perceptions of feeling. These can take on all forms of sensory perception. In addition, there are impressions and information that I gather through research. I listen for reactions, how my own inner intuitive voice, perception and imagination react to, absorb and process external information. Sometimes surprising and unpredictable. This is how I developed the solo Für Saraphia – Jenseits des Schweigens [For Saraphia – Beyond Silence], which premiered in the performative installation flowers, bells and water – decolonizing turns, a project by Chakkars – moving interventions, at schwere reiter in Munich in June 2022.

With the solo, I had planned to pursue my relationship with Saraphia. She worked in my parents’ household before I was born and for some time after I was born. During this time, we lived in Windhoek, South-West Africa, now Nambia. Every now and then my mother would talk about Saraphia. There was a photo of her with me as a toddler. This photo, a bronze handbell, yellow cloth ribbons and a bracelet made of bright kukui nuts, which represented my time in Hawaii, were the props chosen for the rehearsals and ultimately the performance.

I had a very difficult task ahead of me. There was very little information from this early period of my life. I had met Saraphia as a small child. I don’t know what happened to her. The important thing for me was that she belonged to the Ovaherero.

During rehearsals, I entered what I call the space of memory. This space opens up when I enter into an encounter with the actual presence of my own self in the moment. In this space of presence, there is no separation between yesterday and today. Layers open up. Sometimes more permeable, sometimes less. Allowing what shows up, without judgment, is crucial. In the free flow of consciousness, I allowed memories to emerge, which I began to verbalize in the moment. I found the suitable body and hand posture for this. It was the emerging inner images and sensory perceptions that began to formulate themselves as words, as narrative, as concrete poetry. I recorded the first session so that I could watch it again, mainly as an additional support.

My early life emerged, and I started to describe it, sometimes from a bird’s eye view, sometimes from my own inner perspective. In the process of reliving it, an infinite number of tears broke loose, which had been deposited as a somatic layer of pain from the long period of separation. It was overwhelming. But I also knew this from my voice performance experience. Allowing the emotional overwhelm to pass and withstanding it at the same time, the image and narrative of the house we had lived in in Windhoek, the network of roads that spanned the hill, the hilly landscape, would take form in the process of performing. It was remarkable for me to realize that the streets of the district bore the names of German composers … Schubert, Mozart, Beethoven. But also names of birds that are typical of Germany, such as Eulenstrasse.

In a second step, I looked at the photo of Saraphia and myself. I took the pose of Saraphia, who was holding me as a toddler with her left arm and placing a small doll between us with her other hand so that I could hold the doll’s outstretched arm securely. As is the case with toddlers, my gaze was focused on the doll, while Saraphia was looking straight ahead at the camera in a friendly manner. I describe the clothes she is wearing in the photo. And the special headdress with the distinctive flare. A pin adorns the center of the protuberance that runs forward and horizontally to the side. This special headdress is worn proudly by Ovaherero women as part of their traditional dress.During the rehearsal process, I entered into an encounter with Saraphia, got to know her better in the process of somatic-kinesthetic attunement to this photographic snapshot. I entered into the intimacy of this profound somatic experience of having sat on her arm as a small child, with this great closeness. It was infinitely moving to relive how she held me so securely in her arms and held the little doll out to me. During the rehearsal process, this interplay of gestures became a very personal pact that we both realized at the moment of the recording. The little doll, held by both of us, represents for me a loving symbol of hope, of encounter, of humanity and friendship, a friendship that is able to overcome racism and prevailing class asymmetries for a moment (?).

The photograph, of course, marks a different reality. A few months before the photograph was taken, the inhabitants of the Old Shipyard were evicted by the armed arm of the authorities of the ruling apartheid government of South Africa. The Old Dockyard, also known as the Old Location, was a very old settlement of the black population. It was situated on the next hill over from our house. The settlement was destroyed by the authorities with bulldozers. The inhabitants were forcibly relocated to Katutura, a district built outside Windhoek. In the Ovaherero language, Katutura means: the place where we don’t want to live.

In conversations with my mother, which supplemented the rehearsal work, I learned that Saraphia had lived in the old shipyard and from then on had to walk several kilometers from Katutura every morning to continue working with us. The cleared land was sold as good construction land to white settler families who built their spacious houses and gardens there.

Credits: Caroline Armand

In the performance, I went one step further in the encounter. Since Saraphia must have had ancestors who had been affected by the genocide of the German Schutztruppe against the Ovaherero and Nama, I decided to confront myself in spirit with the Omheke Desert. After the Germans had crushed the Ovaherero and Nama uprising in the Battle of the Waterberg on August 11, 1904, the women and surviving men, children and elderly people were driven into the Omheke Desert to die of thirst and starvation. The aim was to eliminate the Ovaherero for good. I decided to give a voice, in excerpts, to the suffering that has been inscribed in the desert as a memory ever since. An incredible undertaking. I placed myself in this sorrowful memory field of the desert, which gripped me again and again with immeasurable shaking. Out of this shaking, I delivered the vocal expression of pure terror with a prolonged, deep, shrill tone and vibrato. The sound reverberates and basically does not stop until the breath stops.

In order to set a sign for the dead, I began to ring a hand-held bronze bell continuously for at least several minutes during the performance. This was to be a sign in memory of the murdered Ovaherero and Nama.

Performed on 25.6.2022 at schwere reiter in Munich as part of Flowers, Bells and Water – Decolonizing Turns, a project conceptualized and organized by CHAKKARs – moving interventions, Munich.

About the author

Monika Lilleike is active as a performance artist, stage director, independent academic researcher and lecturer in the field of Asian and Pacific Performance and European Experimental Performance Art and Theory, residing currently in Berlin. She gained her MFA in Asian Performance at the University of Hawaii at Mānoa/Hawaii (2000). In 2003 Lilleike was invited as a Bunkcho artist fellow to Japan to study with Noh Theater specialist Rick Emmert and Noh Master Sadamu Omura, a member of the Noh Theater Kita Ryu. She took classes on Nihon buyo and Gagaku music learning hichiriki (a double reed instrument) in Tokyo.

During her studies on the island of O’ahu/Hawaii (1997-2001), Lilleike was accepted as a student to the traditionally run Hālau Hula Mele (hula school and ensemble) lead by Hula Master Kumu Hula John Keola Lake. She has been a practicing associate member of Hālau Hula Mele since. Kumu Hula John Keola Lake entitled Lilleike to teach as kumu hula (hula master) perpetuating his hula school in Europe. Lilleike is the head of the traditionally run hula school Hālau Hula Makahikina in Berlin, since 2007. Lilleike perceives her current approach of teaching traditional hula in Germany as a continuous contribution into decolonizing minds, bodies and perspectives towards a comprehensive practice of hula. She gained her PhD in Theatre studies in 2014 at the Free University of Berlin. She published her extensive field research on Hawaiian Hula ‘Ōlapa and her investigation into the method of practice as research at the transcript publishing company in Germany.

Her performance and academic research interests tie into: conditions of oral tradition, practices and aesthetics concerning cultural performance practices from the Pacific and Asia, procedures of cross-cultural translation, the senses and embodiment, stylization and embodied knowledge, the development of practice as research understood as methodological tool of cultural studies and performance analysis, migration, diasporic journeys, politics of identity, critical whiteness studies, and strategies of decolonization. Lilleike discusses her life path and work, developing strategies on transgressing white supremacy in her paper Skinstory – Migratory Experiences and the Transformational Power of Performative Means published as part of the book African Somaesthetics: Cultures, Feminisms, in 2020 at Brills, Netherlands.

Lilleike concentrates in her experimental performance work on the multi-facetted interplay between voice and stylized body movement. The allusive power of gestures, abstract movement figurations and vocal expression in motion make her work seem like concrete poetry. Her performance artistic work is informed by her formal training in classical Chinese, Japanese and Hawaiian performing arts and ties into concepts related to European avant-garde such as Dadaism, Body Art, Minimalism. Lilleike has been involved as a soloist and team player in various music and performance art projects and collaborations throughout the years. As part of her continued investigation into transgressing eurocentrism, Lilleike has been invited lately to participate conceptually and artistically in two installation performance projects run by Chakkars – Moving interventions in Munich. One of them, the production flowes, bells and water – decolonizing turns at the theatre space Schwere Reiter in Munich, included her solo Für Sarafia – Jenseits des Schweigens (2022). At the Asia Pacific Dance Festival and Conference (2022), held at the University of Hawaii and East-West Center, O’ahu/Hawaii, Lilleike presented a paper on decolonial strategies based on measures of “unlearning”. Her second entry was accepted at that same conference, showing the video performance piece Hala – Weaving Sound and Gesture. An Invitation to heal; produced by lilleikewegener, a performance duo run by Lilleike and sound artist and percussionist Bernd Wegener.

url: www.monika-lilleike.de, www.hula-makahikina.de