Rite of Revival: Transforming pain, identities and bondings

We can move forward now

Naked and wounded

And glorified.

We can move on

Bare foot

Raise our head high

And cross the square.

The crossroads of happiness

Freedom and pain.

The crossroads of humility

Of oneness and dignity

And fear.

We are the crossroads

We will cross over our bodies

And reinvent them.

Celebrating pain and survival.

Resurrecting.

Stepping over

Jumping over

From side to side

Over opposite sides

Opposite memories.

We are the here and there

The now and then.

We are Time.

And we are Space.

This space.

The momentary space

Of being and love.

Of being LOVE.

The following is a testimony where I attempt to give a written account of a performative experience that included multiple interweavings with the support of my co-performers: Rite of Revival, a multimedia interactive solo dance performance largely based on interweaving individual and collective identities around the topic of torture, deformation and de-humanization. Conceived in reference to the history and context of Egypt, the performance aimed to re-create the feeling of bonding and togetherness that was lived during the revolution of 25 January 2011, and which can be revived to facilitate the bonding and equality between the spectators versus a history of objectification and exoticised gaze based on race and gender. In this sense the performance was already an interweaving of times, positions and performativities, while being also an interweaving between the individual performer and the collectivity of the spectators, and between each spectator as individual and the rest of the spectators. When performed in Berlin in 2018, the performance acquired two additional layers of interweaving: an interweaving of the foreign performer – myself being Egyptian – with the mostly native German audience, and an interweaving of histories of pain. Therefore new dimensions of interweaving foreignness and spectatorship, and interweaving histories of trauma, were added.

This text is supposed to be accompanied by the audio track of the performance which invites the listener/reader to witness the vocal, musical and poetic experience and to reinvent the performaticity of the performance as an audio piece now.

Rite of Revival was performed in Cairo in December 2017, with support from Tahrir Lounge/Goethe Institute, and with inspiration from Amr Ali’s writing. In February 2018 it was independently re-produced and re-designed with five co-performers from Germany, Austria, and Syria. It was designed as an interactive dance ritual, that on one hand explores the physicality of deformation, mutilation and torture within the choreography and the authored monologue, and on the other hand works on consolidating the community of spectators as an active partner in creating the live performance, its actions and scenography. It was also conceived to have the spectators function as a fundamental part of that ritual, and as a vital part of the human bonding and transcendence that would happen within that ritual which could work as a medium of healing and transformation.

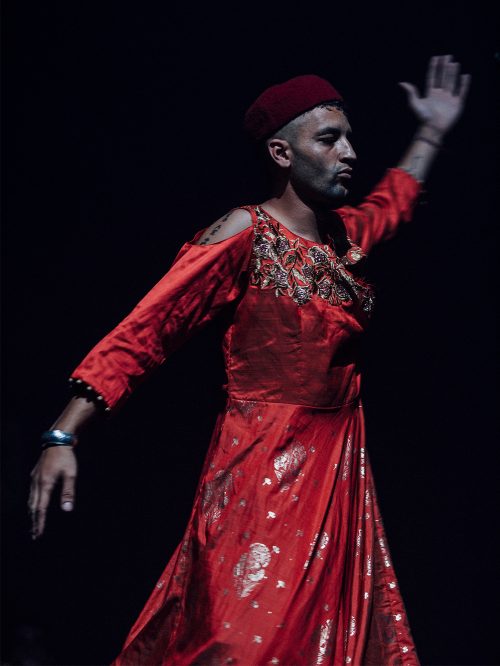

Performed at Gorki Theatre, Studio R, on 22 February 2018, the performance was choreographed, written and designed by myself – supported by co-performers. I also functioned as the central figure, the solo performer projecting the physicality of the tortured body, and later as a medium of interweaving pains, energies and transcendences in order to formulate a collective energy that meets through my presence as a medium or as a catalyst.

Statements from the assistant performers:

Eva Balzer

“I remember the perception of being present in an in-between space, a space where things are real and not real at the same time. A space somewhere between theatre and everyday-life – reality.

This is not the theatre space, yet it is. This is not Berlin/Germany, yet it is, This is not Cairo/Egypt, yet it is. Those are not the people I know (speaking of the people in the audience that I know), yet they are. In that sense truly a liminal space where the order of things is not upheld. I remember upholding synchronically the reality of theatre and the reality of everyday-life.

I remember upholding synchronically a double perception: the one of being connected and the one of being distant. Distant not in the sense of disconnected, but in the sense of being able to perceive myself and the event from outside. A meditative identity – being in and outside the body. An extended arm of Nora and at the same time distanced from her body. Being simultaneously performer and director.

The spectators. Irritated. Out of the comfort zone. Drawn into the circle. Amazed. Distant. Close. Distant. Close. Negotiating their own being within the group of spectators. Wondering who they are and where they are. Drawn into the circle.”

Andre Vollrath

“For me as a performer rehearsing and performing Rite of Revival offered a space where I could get in touch with a lot of difficult emotions such as pain, sadness and fear. It was a space that didn’t evoke and imprison me in these emotions but transform them to a feeling of deep connection and liberation. This was possible because from the beginning on the performance created a circle of community. People were invited to embark on this challenging journey together, not alone as separate individuals sitting in the dark. It was clear that this is not only a performance about Nora Amin, the performer in the centre, but a performance about us, about a shared, deep suffering and the whole set up communicated this in a very courageous way.

In the beginning I could see a lot of irritation and insecurity in the eyes of many spectators. It seemed to take some time for them to enter this world and to open up to an experience that didn’t seem to match their expectations and the theatre codes they might know. However in the course of the performance there was a very strong shift of energy. People seemed to soften, to enter a state of flow and communal sharing. The shape of a circle, the projections, the shared cloth, the ongoing music, Nora Amin’s performance made it almost impossible to stay out of this universe.

As performers part of our role was to be in energetic contact with each other and Nora Amin in the centre in order to create an energetic network or frame that supports the experience of the spectators. This partially was a challenging task for me as we were also busy with guiding the spectators and hadn’t yet incorporated all the necessary steps in the short time of rehearsal.

I felt that the set up of the ritual and Nora Amin’s performance were so strong that it could easily cope with these losses of attention and insecurities. Nevertheless from time to time in this premiere I wished to be part of the spectators to be able to fully let go and just receive this wonderful experience.”

Pasquale Rotter

“As a co-performer I assisted Nora Amin in literally wrapping the audience into a circular arranged space of unwrapping the trauma, living through it and eventually transform and heal it – a ritual. It was a space that felt held and restricted at the same time, as we need to create intense and intimate connection as well as clarity on the frame in order to hold space for this kind of performative ritual and everyone involved. Our connection – in the form of a white sheet – mirrored the pain, the shock, the strength… through projecting back on us performers, through shadow and light. However there was no place for hiding, for nobody. Being positioned in a circle, symmetrical with the other co-performers gave me a sense of holding space while also touching time-relevant aspects of trauma on the one hand. And created a connection to Nora Amin that was beyond time, space and alignment on the other hand. Performing this piece as a Black Austrian woman in Germany, a place with particularly strong bonds to denial, order, hierarchy, severity and disembodiment (just to name a few of relevant destructive forces), was a truly empowering experience that left lasting hope for social change.”

Note from the creator of the performance:

The performance was designed and conceived as a ritual for several reasons:

– It was inspired from the circular shape connected to rituals that are based in my Arab and Egyptian cultures, whether Halaka or Zar or street performances or Hadra. The community gathering in a circle, or in circles, was somehow a definition of the spatial aspect of a ritual.

– It relied on a strong concept of energy communication, circulation, channeling and projection. The circle facilitated and supported the energy circulation, and created a bonding between the participants/ spectators, a bonding that defines the nature of a collective ritual and therefore lays the foundation for a human equal and connected community that creates the ritual and develops it.

– It was designed with very specific, systematic and calculated actions that have to be repeated in a regular, sustained and rhythmic style. Because every ritual includes repetition, repeated actions, and a kind of collectively adopted physical behaviour, the spectators’ actions took the shape of almost similar repetitive individual actions that all two hundred spectators repeat. At the same time those individual actions are passed on from one person to the other, and communicated and connected from one person to the other, so that there happens a kind of individual internal partnership between each two spectators. From one to the other to the last person this constructive and repetitive cooperation builds a collective active physicality, and a community that ends by adding visual aspects to the performance due to the material fabric that they pass on from one to the other and that ends by becoming a part of the scenography of the performance via the hands and arms of the spectators holding it, eventually connecting through it from the first till the last person. On the performative level the actions of passing on the fabric till it makes a circular shape held by everybody becomes an active performative action made by the spectators to translate the human and emotional bonding into a material representation (via the white fabric) which also could be interpreted as a symbolised visualisation of wrapping the pain, of materialising each person’s story, and of changing the way that the space looks.

On one hand, the practises of dance and performance are here opened to the spectators who literally become active partners and collaborators in creating the ritual and its togetherness, and on the other side the practices

are here primarily giving space to the spectators’ actions that interweave through the medium of the fabric, and through what the fabric carries of their emotions and personal projections, and of the way they hand it to one another, until they hold it up together to make it into a circular screen for the video projections. Therefore the spectators employ and develop their collective actions to create a new scenographic aspect to the performance, one that clearly holds witness and shows visual references of a testimonial act.

All the actions of the spectators are facilitated by co-performers or assistant performers, five of them, who function as ceremony helpers within this ritual, who wear the same fabric and colour, and who hold a strong bonding between each other, and with me, the solo performer. Their energy channeling and bonding holds and carries the space and regulates the collective energy of the spectators, and the bonding that the five co-performers share with me guarantees a network and radiant flow that covers the whole circle and tightens the communication and communal transcendence.

Nevertheless all this was not what the audience expected when buying tickets for a performance created by an Egyptian woman. Maybe some of them did already know my work, and considered the performance as artistic work without any labels, but definitely another part of the audience had expectations related to the label, the label of the migrant body, the gendered body, the Arab body, and therefore – maybe – the exotic body. My first intention was not to create a performance that decolonizes my body, or decolonizes the spectators’ perceptions, my initial intention was to create a dance ritual of reviving pain and going towards healing. It was part of my life long project on Performing Trauma, which later brought me to a Valeska-Gert guest professorship. It was also an intention of reviving the feeling of community among the spectators as a microcosm of the larger society. But how would I do that if I already had a stigmatised body and a labeled identity…? How would I be able to create a dance practise of interweaving, of transcendence and of human bonding if my very presence was already connected – or triggering – a history and consciousness of divide, discrimination, hierarchy and voyeurism, how can I stimulate the spectators to leave their Western and white position of spectatorship and re-position themselves as one with me? As equal humans…?

The explorations that followed were gigantic in the final formulation of my understanding of my role as a performer, and in the performance’s understanding of the spectators’ gaze towards me, the solo female performer. This final formulation included the revelation that I should reverse my position from being looked at, to be looking back to the spectators, to look back is to create equality in the gaze, is to see the spectators, and allow them to realise that they are also being looked at, it creates mutuality, removes separation and hierarchy, and transforms the act of looking/gazing into an act of exchanging and sharing. I should re-position myself and become also a spectator of the ritual, a spectator of the spectators, then the whole concept of spectatorship and the gaze would shift into a dimension of equality and human exchange, which welcomes the instant messages being sent and received, those messages that shape the momentary energy flow and growth of the performance.

Then another crucial revelation came with a final part of the performance where I have a one on one encounter with each spectator, I pass through all the circles of spectators and look through the eyes of each spectator along with a hand to hand caress that brings an immediate physical and sensorial dimension to the relation with the spectator, recognises the emotional bonding, removes the hierarchy and the alienation, and radiates humanness which replaces a history of othering and of objectification, and eventually opens a path towards healing via the communal spirit and the collective human bonding.

At the end, I disappear and the spectators gather the fabric and put it in my place, and leave the space in groups. They hopefully end by owning the ritual, and by re-identifying with the power of performance as ritual, and the power of the community, it is this power that is able to decolonise the migrant performer body only by first decolonising the body – bodies – of the spectators through reviving their human bonding to each other and therefore to the migrant performer- who would no longer be migrant – and to the performance that would no longer be labeled as an import.

Rite of Revival

A Multimedia Interactive Solo Dance Performance

Scripted, performed & directed by Nora Amin

With co-performers: Eva Balzer, Pasquale Rotter, Alina Amer, Julia Lemmle & André Vollrath

Live drums & kajoon: Tamer Essam

Recorded violin: Ayman Asfour (and composition)

Sound track design and composition: Nader Sami

Sound, light and video technician: Maged Monir

Video design: Ibrahim Ghareib

Presented at Studio R, Maxim Gorki Theater

22 February 2018

Suggested Citation

Amin, Nora. 2021. “Rite of Revival” In: Moving Interventions 1: Ambiguous Potentials // Performative Awakenings, December 2021. Edited by / Herausgegeben von: Sarah Bergh and Sandra Chatterjee, with Ariadne Jacoby (CHAKKARs – Moving Interventions), copyedited by: Veronika Wagner. Published by / Veröffentlicht von CHAKKARs – Moving Interventions.

About the author

Egyptian performer, choreographer, theatre director & author living in Berlin. In her choreographic work and in her writing/research, she adopts a feminist perspective and searches for personal authorships and signatures that can transform dance/performance into either a political medium of resistance or a field of intersectional healing. Throughout her work, she uses critical discourse to dismantle colonial patterns recycled in dance pedagogy and knowledge, or to construct an authentic choreographic language that reflects on the journey of identity through oppression, objectification and shaming. Her most recent book, Dance of the Persecuted, reconstructs the history of Baladi dance in Egypt from a feminist perspective linking coloniality with capitalism and patriarchy. Founder of the nation-wide Egyptian Project for Theatre of the Oppressed and its Arab network (Lebanon, Morocco & Sudan), board member of the German Centre of the International Theatre Institute, and member of the scientific & advisory board of the Barba Varley Foundation in Denmark. (Photo by Ehab Abdellatif)

Nora Amin

Berlin